This is stanza # 3 of 4 numbered stanzas, I was struck, real struck, by the line, A man's a beast prowling in his own house...

How terrible the need for solitude:

That appetite for life so ravenous

A man's a beast prowling in his own house,

A beast with fangs, and out for his own blood

Until he finds the thing he almost was

When the pure fury first raged in his head

And trees came closer with a denser shade.

- From "The Pure Fury" by Theodore Roethke

Thursday, December 5, 2013

Friday, August 30, 2013

Heaney's journey to Aarhus

August 30, 2013 - Heaney died today. This is an excerpt, with some lines from the poet, from an unpublished essay I wrote about, among other things, my encounter with Ötzi the Iceman:

I’ve always loved old bones. I love their mystery, the tactile connection they represent to personal histories, so close yet so obscure. For me there has been no bigger thrill than peering into a gaping, ruined grave in Enniskillen to spy in the shadows an old browned skull and to imagine, just for a moment, just a sound the brain it held might have produced, just one emotion, one sensation. And if old bones were thrilling, then old faces, old noses, old fingernails and old whiskers were even better. Although I’d found they could disappoint, too. Once I had walked the long, grim, subterranean corridors of a monastery in Palermo where hundreds of dried mummies of all ages, dressed in their burial clothes, gazed back at me. Their poses bordered on clownishness and their display amounted to a violation, like a deprivation of promised sleep. They should have delivered me to a morbid nirvana. Instead they left me unmoved.

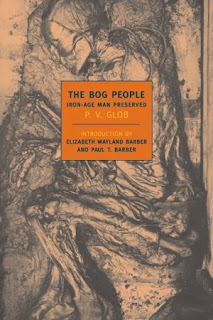

Then I read P.V. Glob’s classic, The Bog People (from the miraculous New York Review of Books imprint), about the fully-preserved Iron Age corpses found in bogs in Denmark and Ireland, men who were criminals, young women who were adulterers or in some cases sacrifices to the gods. I could spend an entire afternoon staring at photographs of the tormented, peat-stained, human face of the Tollund Man, his impressively aquiline nose, the vertical crease of mortal anguish in his forehead, the hangman’s noose around his neck still. I had read and re-read the poems the bog mummies had inspired in Seamus Heaney. For the poet, the Tollund Man, the Grauballe Man, the Bog Queen, and the brutality and cruel, ignorant sacrifice to which they bore witness, became useful symbols for the violent, religion-fueled predicament of the Irish of the 1970s. Here he would leave behind snipes and drowned farm cats as symbols and turn to something more ambiguous and better. “Opening The Bog People,” he told Dennis O’Driscoll, “was like opening a gate."

Through them Heaney could exercise his gift for ruthless identification and self-reflection. It’s all there in a bog poem called “Punishment,” with passages like these:

This desire I feel and draw I find in Ötzi Heaney describes precisely in these stanzas from “Tollund Man:"

Heaney dreamed of a journey to Denmark to see the Tollund Man, like mine to Italy to see the Iceman; I happen to know he made it. I could think of few better fates for a corpse than to become the inspiration for a poem, or a journey to Aarhus, by Seamus Heaney. And all Ötzi gets is me.

-from "The Find"

I’ve always loved old bones. I love their mystery, the tactile connection they represent to personal histories, so close yet so obscure. For me there has been no bigger thrill than peering into a gaping, ruined grave in Enniskillen to spy in the shadows an old browned skull and to imagine, just for a moment, just a sound the brain it held might have produced, just one emotion, one sensation. And if old bones were thrilling, then old faces, old noses, old fingernails and old whiskers were even better. Although I’d found they could disappoint, too. Once I had walked the long, grim, subterranean corridors of a monastery in Palermo where hundreds of dried mummies of all ages, dressed in their burial clothes, gazed back at me. Their poses bordered on clownishness and their display amounted to a violation, like a deprivation of promised sleep. They should have delivered me to a morbid nirvana. Instead they left me unmoved.

|

| The Bog People by P.V. Glob |

Through them Heaney could exercise his gift for ruthless identification and self-reflection. It’s all there in a bog poem called “Punishment,” with passages like these:

I who have stood dumb

when your betraying sisters,

cauled in tar,

wept by the railings,

who would connive

in civilized outrage

yet understand the exact

and tribal, intimate revenge.

This desire I feel and draw I find in Ötzi Heaney describes precisely in these stanzas from “Tollund Man:"

Some day I will go to Aarhus

To see his peat-brown head,

The mild pods of his eyelids,

His pointed skin cap,

In the flat country nearby

Where they dug him out,

His last gruel of winter seeds,

Caked in his stomach...

Heaney dreamed of a journey to Denmark to see the Tollund Man, like mine to Italy to see the Iceman; I happen to know he made it. I could think of few better fates for a corpse than to become the inspiration for a poem, or a journey to Aarhus, by Seamus Heaney. And all Ötzi gets is me.

-from "The Find"

Thursday, August 22, 2013

A vessel on the sea, at midnight, in a storm - Poe's "Alone"

.jpg) |

| Combine the names "Booth" & "Poe" - and you get..."Both" |

However, I couldafford The Raven and the Whale, Perry Miller's dissection of the mid-19th Century American literary scene, especially in New York, its cattiness, its brawling, its factionalism, the births and deaths of its many journals, their great achievements and great failures, all their explicit scheming for an American Literature independent of English influence. How in service to this elusive American ideal -- the country was only 60 years old, technically -- the editors, writers and intellectuals, especially in New York, searched and begged and hedged and compromised, how they boosted any old tripe if it seemed American and new. And how, when what Duyckink and Matthews and their colleagues were looking for came, in the works of Melville, Whitman and Poe, they just didn't see. To be sure, they published and honored particularly Poe and Melville, and welcomed all three of them into their factions when they could be useful.

But they were blind to the fact that in their own time and city, the pillars of American literature had finally appeared. (Similarly, a couple of decades later, Col. Wigginson was incredibly supportive of that fourth pillar, Emily Dickinson, was a friend to Emily, but couldn't see the monumental achievement right before his eyes.)

Another Metcalf source I could find and afford was Frances Winwar's life of Poe, The Haunted Palace. And so I spent a few days in stunned contemplation of the abject sadness of Poe's existence. For years I have been known to mutter, seemingly out of nowhere, "Poor Herman," when suddenly comes to mind how poorly things ended up for Melville. But Poe's life, the constant death and early loss, the bitter avarice of his guardian, then the late death and loss, the addiction and the final, deep mental illness, trump Herman's own unsatisfying fate. Amazing how much Poe produced. How many magazines he catapulted to success. But always in the end something would break. I guess it is ironic, that his towering ambition was warranted, but often it was what caused him to crash, to have so start again from literary, financial and emotional scratch.

.jpg) |

| Metcalf, Winwar, Zagajewski, Poe (ed., Wilbur), Miller |

And then, just as I was moving on to other things, while reading Adam Zagajewski's poem, "The Generation," I came across these lines, which reminded me again of Poe's "Alone":

Two kinds of death circle about us.One puts our whole group to sleep,takes all of us, the whole herd...

...the other one is wild, illiterate,it catches us alone, strayed,we animals, we bodies, we the pain,we careless and uneducated...We worship both of them in two religionsbroken by schism...-Adam Zagajewski"The Generation"

Here is the Poe poem, also about two kinds of death. In its final image, it seems like Poe is characterizing his entire life, his haunted mind, the warp of his works. It's interesting about the warp of his stories and characters; it lurked always in their depths, only slowly to be revealed by the storyteller, often slowly to destroy him, as it did Poe.

Winwar ends her biography with a dream Walt Whitman described to a group of friends after a memorial for Poe at his re-burial in 1875. Whitman had met Poe a couple of times. Poe had been one the earliest publishers of Whitman's poetry, pre-Leaves of Grass. In Whitman's vision, he sees a "vessel on the sea, at midnight, in a storm... On the deck was a slender, slight, beautiful figure, a dim man, apparently enjoying all the terror, the murk and the dislocation of which he was the center and the victim. The figure of my lurid dream might stand for Edgar Poe, his spirit, his fortunes, and his poems..."

To Winwar, writing in 1959, the figure was Poe, but also Poe as Modern Man, "conscious of a new dimension: the world within, whose storms, terrible in their revealing flashes, throw light, now more than ever, on the black, hidden regions of the soul."

Makes sense to me. Okay, here's Poe's poem, finally (note the italicized second "I" in line 8):

Alone

From childhood's hour I have not been

As others were -- I have not seen

As others saw -- I could not bring

My passions from a common spring --

From thw same source I have not taken

My sorrow -- I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone --

And all I lov'd -- Iloved alone --

Then -- in my childhood -- in the dawn

Of a most stormy life -- was drawn

From ev'ry depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still--

From the torrent, or the fountain --

From the red cliff of the mountain --

From the sun that 'round me roll'd

In its autumn tint of gold --

From the lightning in the sky

As it pass'd me flying by --

From the thunder and the storm--

And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view--

Friday, August 16, 2013

Another poem by R.S. Thomas

Tell me, what did Shelly dream? And how did love deceive him?

Song at the Year's Turning

Shelley dreamed it. Now the dream decays.

The props crumble. The familiar ways

Are stale with tears trodden underfoot.

The heart's flower withers at the root.

Bury it, then, in history's sterile dust.

The slow years shall tame your tawny lust.

Love deceived him; what is there to say

The mind brought you by a better way

To this despair? Lost in the world's wood

You cannot stanch the bright menstrual blood.

The earth sickens; under naked boughs

The frost comes to barb your broken vows.

Is there blessing? Light's peculiar grace

In cold splendour robes this tortured place

For strange marriage. Voices in the wind

Weave a garland where a mortal sinned.

Winter rots you; who is there to blame?

The new grass shall purge you in its flame.

R.S. elsewhere on the blog: "Somewhere"

|

| 1963 edition, dedicated to the great James Hanley |

Shelley dreamed it. Now the dream decays.

The props crumble. The familiar ways

Are stale with tears trodden underfoot.

The heart's flower withers at the root.

Bury it, then, in history's sterile dust.

The slow years shall tame your tawny lust.

Love deceived him; what is there to say

The mind brought you by a better way

To this despair? Lost in the world's wood

You cannot stanch the bright menstrual blood.

The earth sickens; under naked boughs

The frost comes to barb your broken vows.

Is there blessing? Light's peculiar grace

In cold splendour robes this tortured place

For strange marriage. Voices in the wind

Weave a garland where a mortal sinned.

Winter rots you; who is there to blame?

The new grass shall purge you in its flame.

R.S. elsewhere on the blog: "Somewhere"

Saturday, July 13, 2013

Friday, July 12, 2013

Poem by Desmond O'Grady

This is one of those poems, like R.S. Thomas' "Song at the Year's Turning," that I can't really figure out but love very much anyway. I love "fisted flex of heart." Also how "staring staring silence" is revisited later with the "Unwinking eyes of saints" and "I felt the Churcheyed, fidget fear." I love the structure of the three long sentences that make up the three stanzas, and the tone of frustration, perhaps tinged with surrender. Perhaps not tinged with surrender. I'm not really sure. I like the outraged shock in the question of the title. Is it outraged shock? Is it a sort of mocking of teenage petulance? There's some kind of returning going on, but is it to an emotion? Or a place? And if it's to a place, is it a physical place or a spiritual one? Maybe it's all of these things. Or none of them. I can't really figure it out. But still I love this poem by the Irishman, Desmond O'Grady, which I found in his 1967 collection called The Dark Edge of Europe.

Was I Supposed to Know?

When,

In a blue-sharp, fallow sky,

With wind in hair

And grey of rock, angled by ages, sharpening the eye,

I

Stamped down that cut stone stair

Towards sand and sea

And clawed, nails scratching, down from the deaf-mute cliffs to where

Were track and trees below --

Was I supposed to know?

When,

With senses quick as compass

And tightened skin,

In breaking clearing, fell on Church and Churchyard moss

I,

Helpless, toeheeled in

To Christ and Cross

And staring staring silence, felt small as a pin,

Felt schoolboy years ago --

Was I supposed to know?

Was I supposed to know

That each fisted flex of heart

And wide of eye,

Each pitch of thought in bone-sprung skull; each stutter start

Of unravelled blood in my

Knit flesh and bone;

And every studied part I cast me as a boy;

That all my rebel scorn

And mock at prayer,

My every bedded bitch and spilled out kids unborn,

Were

All marked mine with care --

By some high Law

Or some high guiding Plan -- to lead me back to where,

Again,

With coffin smell of pew

And chris of Cross,

Unwinking eyes of saints and hushed confession queue --

For one loud nervous boot

Of frightened heart,

I felt the Churcheyed, fidget fear of schooltied youth?

Wednesday, June 19, 2013

More Chekhov, more on books

This paragraph from a Chekhov short story describes something of how I read. The first and last sentences sound particularly familiar. Are these the last years of my confinement? What am I confined in? Life and consciousness and failure. Could books save me? (With the passage's final image, I was reminded of Ishmael clinging to Queequeg's coffin.) Ultimately, they destroy the prisoner in the story. Books, and his years of solitude, turn him into a cynic, a misanthrope, a Timon. Is Chekhov saying that if you knew humanity only through its books, you would want to avoid it in real life? Is he saying that that conclusion would be accurate? And if so, is he blaming humanity for this outcome, or just writers of books, like himself?

-Anton Chekhov

"The Bet"

During the last years of his confinement the prisoner read an extraordinary amount, quite haphazard. Now he would apply himself to the natural sciences, then he would read Byron or Shakespeare. Notes used to come from him in which he asked to be sent at the same time a book on chemistry, a textbook of medicine, a novel, and some treatise on philosophy or theology. He read as though he were swimming in the sea among broken pieces of wreckage, and in his desire to save his life was eagerly grasping one piece after another.

-Anton Chekhov

"The Bet"

Monday, May 13, 2013

Books: the way of the horse

It wouldn't be a terrible fate; everybody loves horses. But I think someday print books will have gone the way of horses, once not too too long ago so essential in so many ways, now a curiosity, a luxury, a pleasure to see but few of us ever really get near them or need them. Someday there will be people among us who own books (horses), who read books (ride horses) regularly. And, like horse people today, book people will be seen as sort of interesting for that slightly exotic bit of culture they experience with their books (horses) and all their book-(horse)-friends. Some of us will envy them their special interest and the activity of reading (riding) and caring for their books (horses) and that extra bit of knowledge they have about types (breeds) of books (horses) and how to handle a book (horse). Having grown up around books (horses), many of their children will have learned to love books (horses) and will come to have their own. Nearly everyone will at some time in his or her life have read a book (ridden a horse), on vacation at a fancy resort or while visiting a family friend who keeps a few. Some will find they enjoy being around books (horses) and reading books (riding horses) but will never come to own one. Perhaps they will be prohibitively expensive to own. Perhaps some will find they are allergic to books (horses), or frightened of them. I think I will be dead by the time this happens, but perhaps not for long.

Wednesday, March 6, 2013

From Kickham's Knocknagow

Irishman C.J. Kickham's 19th Century novel Knocknagow is exceedingly charming and often very funny. That's why this dead-serious, grisly passage, which I read last night, came as a shock. I happen pretty much by accident to be reading Knocknagow immediately after finishing Thomas Flanagan's great historical novel, The Year of the French, about the bleak and bloody 1798 uprising of the Irish, with some aid from the French, against their English overlords. Knocknagow is set some decades later, but a couple of veterans of '98 populate the book, and the '98 Uprising has become part of the consciousness of many of the younger characters as well. Here we learn the reason that Mrs. Donovan (mother to Mat the Thrasher, local hero for his good looks, good nature, and hurling prowess) tends to have a sad face, which the narrator calls "the shadow of a curse." The soldiers referred to are English Red Coats, although some of them may well have been native Irish. The yoemen are local troops loyal to the crown.

Poor Mrs. Donovan got that sad face of hers one bright summer day in the year '98 when her father's house was surrounded by soldiers and yeomen, and her only brother, a bright-eyed boy of seventeen, was torn from the arms of his mother, and shot dead outside the door. And then a gallant officer twisted his hand in the boy's golden hair, and invited them all to observe how, with one blow of his trusty sword, he would sever the rebel head from the rebel carcase. But one blow, nor two, nor three, nor ten, did not do; and the gallant officer hacked away at the poor boy's neck in a fury, and was in so great a passion that when the trunk fell down at last, leaving the head in his hand, he flung it on the ground, and kicked it like a football; and when it rolled against the feet of the horrified young girl, who stood as if she were turned to stone near the door, she fell down senseless without cry or moan, and they all thought she too was dead. She awoke, however, the second next day following, just in time to kiss the poor bruised and disfigured lips before the coffin-lid was nailed down upon them.

Monday, January 7, 2013

Prose passage from Osip Mandelstam

The Russian Osip Mandelstam, vindictively exiled by Stalin for the second and final time in 1938, died in a Siberian transit camp, reportedly out of his mind. He is known for his poetry, but wrote great, rich, dense, evocative essays and stories about Russian life in St. Petersburg and elsewhere. These two paragraphs (translated by Clarence Brown) are a perfect example. ("Scellé" means sealed. I don't know the "Song of Malbourk," although I have been to the amazing Malbork Castle, in Poland, and it is sometimes spelled "Malbourk.")

From "Riots and Governesses:"

It is my opinion that the little songs, models of penmanship, anthologies, and conjugations had ended by driving all these French and Swiss women themselves into an infantile state. At the center of their worldview, distorted by anthologies, stood the figure of the great emperor Napoleon and the War of 1812; after that came Joan of Arc (one Swiss girl, however, turned out to be a Calvinist), and no matter how often I tried, curious as I was, to learn something from them about France, I learned nothing at all, save that it was beautiful. The French governesses placed great value upon the art of speaking fast and abundantly and the Swiss upon the learning of little songs, among which the chief favorite was the "Song of Malbourk." These poor girls were completely imbued with the cult of great men -- Hugo, Lamartine, Napoleon, and Molière. On Sundays they had permission to go to mass. They were not allowed to have acquaintances.

Somewhere in the Ile de France: grape barrels, white roads, poplars -- and a winegrower has set out with his daughters to go to their grandmother in Rouen. On his return he is to find everything "scellé," the presses and vats under an official seal. The manager had tried to conceal from the excise tax collectors a few pails of new wine. They had caught him in the act. The family is ruined. Enormous fine. And, as a result, the stern laws of France make me the present of a governess.

From "Riots and Governesses:"

It is my opinion that the little songs, models of penmanship, anthologies, and conjugations had ended by driving all these French and Swiss women themselves into an infantile state. At the center of their worldview, distorted by anthologies, stood the figure of the great emperor Napoleon and the War of 1812; after that came Joan of Arc (one Swiss girl, however, turned out to be a Calvinist), and no matter how often I tried, curious as I was, to learn something from them about France, I learned nothing at all, save that it was beautiful. The French governesses placed great value upon the art of speaking fast and abundantly and the Swiss upon the learning of little songs, among which the chief favorite was the "Song of Malbourk." These poor girls were completely imbued with the cult of great men -- Hugo, Lamartine, Napoleon, and Molière. On Sundays they had permission to go to mass. They were not allowed to have acquaintances.

Somewhere in the Ile de France: grape barrels, white roads, poplars -- and a winegrower has set out with his daughters to go to their grandmother in Rouen. On his return he is to find everything "scellé," the presses and vats under an official seal. The manager had tried to conceal from the excise tax collectors a few pails of new wine. They had caught him in the act. The family is ruined. Enormous fine. And, as a result, the stern laws of France make me the present of a governess.

Tuesday, January 1, 2013

Perfect little poem by Henry Taylor

Henry Taylor was a professor in the Lit Department at American University in D.C. when I was a student there in the late Eighties. He was my independent study adviser my senior year. I don't think he was much impressed with me, but was always very kind about it. I love this poem and think of it all the time, partly because it is brief enough for me to remember it, but more because he gets everything right in it (even down to the colon at the end of line 2). I think I recognized this even when I was young, but now, no longer young, I experience the poem in a way I wouldn't have then. It's from his 1985 Pulitzer Prize winning volume, The Flying Change. Here's how he inscribed my copy after an appearance before a great class I took my sophomore year with Robert Bausch called The Living Writers:

For Jim,

With thanks for good questions and kind words --

All best,

Henry Taylor

25 March 88

The poem:

For Jim,

With thanks for good questions and kind words --

All best,

Henry Taylor

25 March 88

The poem:

Airing Linen

Wash and dry,

sort and fold:

you and I

are growing old.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

.jpg)