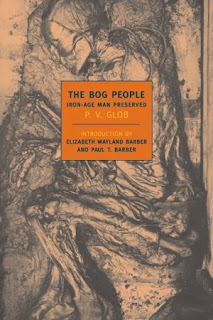

.jpg) |

| Combine the names "Booth" & "Poe" - and you get..."Both" |

It started with the idle late night plucking from my bookshelves Paul Metcalf's Both, one of his many strange, imaginative, hybrid works. In this one, he documents the unexpected, ostensible parallels between Edgar Allan Poe and John Wilkes Booth, and not just in their appearances, signatures, and melodramatic personalities. Metcalf's list of sources for Bothwas so interesting that I began tracking them down, at least the one's I could afford. Some were so obscure that, even if I could find them on abebooks, I could never have afforded them. I really wanted to pull the trigger on The Mad Booths of Maryland, but at over $400, it'll just have to wait.

However, I couldafford The Raven and the Whale, Perry Miller's dissection of the mid-19th Century American literary scene, especially in New York, its cattiness, its brawling, its factionalism, the births and deaths of its many journals, their great achievements and great failures, all their explicit scheming for an American Literature independent of English influence. How in service to this elusive American ideal -- the country was only 60 years old, technically -- the editors, writers and intellectuals, especially in New York, searched and begged and hedged and compromised, how they boosted any old tripe if it seemed American and new. And how, when what Duyckink and Matthews and their colleagues were looking for came, in the works of Melville, Whitman and Poe, they just didn't see. To be sure, they published and honored particularly Poe and Melville, and welcomed all three of them into their factions when they could be useful.

.jpg) |

| This book will make you read Herman and Edgar anew |

But they were blind to the fact that in their own time and city, the pillars of American literature had finally appeared. (Similarly, a couple of decades later, Col. Wigginson was incredibly supportive of that fourth pillar, Emily Dickinson, was a friend to Emily, but couldn't see the monumental achievement right before his eyes.)

Another Metcalf source I could find and afford was Frances Winwar's life of Poe, The Haunted Palace. And so I spent a few days in stunned contemplation of the abject sadness of Poe's existence. For years I have been known to mutter, seemingly out of nowhere, "Poor Herman," when suddenly comes to mind how poorly things ended up for Melville. But Poe's life, the constant death and early loss, the bitter avarice of his guardian, then the late death and loss, the addiction and the final, deep mental illness, trump Herman's own unsatisfying fate. Amazing how much Poe produced. How many magazines he catapulted to success. But always in the end something would break. I guess it is ironic, that his towering ambition was warranted, but often it was what caused him to crash, to have so start again from literary, financial and emotional scratch.

.jpg) |

| Metcalf, Winwar, Zagajewski, Poe (ed., Wilbur), Miller |

And so I opened again the poems of Poe, including a volume edited, and with a helpful introduction by the great American poet Richard Wilbur. One particular poem, "Alone," stayed with me for awhile.

And then, just as I was moving on to other things, while reading Adam Zagajewski's poem, "The Generation," I came across these lines, which reminded me again of Poe's "Alone":

Two kinds of death circle about us.

One puts our whole group to sleep,

takes all of us, the whole herd...

...the other one is wild, illiterate,

it catches us alone, strayed,

we animals, we bodies, we the pain,

we careless and uneducated...

We worship both of them in two religions

broken by schism...

-Adam Zagajewski

"The Generation"

Here is the Poe poem, also about two kinds of death. In its final image, it seems like Poe is characterizing his entire life, his haunted mind, the warp of his works. It's interesting about the warp of his stories and characters; it lurked always in their depths, only slowly to be revealed by the storyteller, often slowly to destroy him, as it did Poe.

Winwar ends her biography with a dream Walt Whitman described to a group of friends after a memorial for Poe at his re-burial in 1875. Whitman had met Poe a couple of times. Poe had been one the earliest publishers of Whitman's poetry, pre-Leaves of Grass. In Whitman's vision, he sees a "vessel on the sea, at midnight, in a storm... On the deck was a slender, slight, beautiful figure, a dim man, apparently enjoying all the terror, the murk and the dislocation of which he was the center and the victim. The figure of my lurid dream might stand for Edgar Poe, his spirit, his fortunes, and his poems..."

To Winwar, writing in 1959, the figure was Poe, but also Poe as Modern Man, "conscious of a new dimension: the world within, whose storms, terrible in their revealing flashes, throw light, now more than ever, on the black, hidden regions of the soul."

Makes sense to me. Okay, here's Poe's poem, finally (note the italicized second "I" in line 8):

Alone

From childhood's hour I have not been

As others were -- I have not seen

As others saw -- I could not bring

My passions from a common spring --

From thw same source I have not taken

My sorrow -- I could not awaken

My heart to joy at the same tone --

And all I lov'd -- Iloved alone --

Then -- in my childhood -- in the dawn

Of a most stormy life -- was drawn

From ev'ry depth of good and ill

The mystery which binds me still--

From the torrent, or the fountain --

From the red cliff of the mountain --

From the sun that 'round me roll'd

In its autumn tint of gold --

From the lightning in the sky

As it pass'd me flying by --

From the thunder and the storm--

And the cloud that took the form

(When the rest of Heaven was blue)

Of a demon in my view--

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)